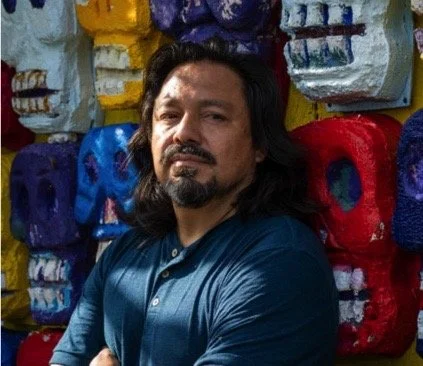

Artist Spotlight: César Viveros

César Viveros is an artist and muralist from Veracruz Mexico who has been collaborating with Mural Arts Philadelphia since 2000. He uses his art to tell the stories of communities and their ideology. Vivero is a valued figure in the Philadelphia art community and one of over 100 artists working on the Ministry of Awe Bank. This week we sat down with César to learn about his artistic journey and connection to immigration stories.

What inspired you to become an artist, and how did you find your way into public and community-based art?

I’m originally from Veracruz, Mexico, and I was influenced a lot by my surroundings. Veracruz is very humid, tropical, and full of pre-Hispanic civilizations, some dating 1,500 years before Jesus. Growing up, my father would take my brother and me to work in the fields, and we’d find small clay artifacts while digging. My brother explained they came from ancient people who lived there before the Spanish conquest. Finding those pieces sparked my imagination.

Clay became my first artistic medium—there was clay everywhere. As a child, I would sculpt constantly. Kids even traded toys with me for my clay figures. By middle school, teachers would select me and my friends to paint murals for school festivals. By high school, my friend and I had a small business painting advertisements. This was before the internet era, so we gained lots of practice.

When I came to Philadelphia, I tried to get into galleries, but realized I was looking in the wrong place. Then I discovered the Mural Arts Program [now Mural Arts Philadelphia], and I met Meg Saligman, who gave me the opportunity to assist her. Through that, I learned that public art is about telling other people’s stories, not just my own. That’s how I found my path into community-based art.

How do you decide what stories deserve to be brought to life through your murals?

Most of the murals I’ve done in Philadelphia are about other people’s stories. Mural Arts receives funding from organizations and donors, and the purpose is always to reflect the community. Murals are the “poor person’s power;” after TV, radio, and newspapers fail to tell your story, a mural can. I listen carefully to people’s stories and create my own interpretation through my brushstrokes and images. Public work still leaves room for creativity and imagination. But I also make time to create personal work—murals I painted when I was young were very personal, though many were erased later. Public art can be fleeting.

“Murals are the “poor person’s power;” after TV, radio, and newspapers fail to tell your story, a mural can.”

What does Día de los Muertos mean to you personally and creatively?

Part of my work is connecting who I was in Mexico with who I am here. As an immigrant, I advocate for immigrant rights. We come out of necessity, but we contribute culturally. Our heritage is 3,500 years old—it’s embedded in us. Through art, we present ourselves.

Day of the Dead is probably the most important tradition we have. It’s deeply Mexican and

is formed by Mesoamerican traditions mixed with Spanish influence. My personal connection comes from my wife, who used to make large papier-mâché sculptures and processions. I learned from her, especially after realizing cement sculptures were too heavy for people to help me carry. Papier-mâché allows me to create large, ephemeral pieces. They may only last once, but I love that they exist in the present moment. Around October, I always get busy with commissions and invitations to create Day of the Dead installations.

This was my third year doing Day of the Dead at FDR Park in Philadelphia. Previously, I built altars at the top of the staircase by the lake, inspired by the Templo Mayor in Mexico City. But this year, I proposed a site-specific piece at the bottom of the stairs, using soil to build a platform resembling a Veracruz-style cemetery. In Veracruz, altars are small, but cemetery visits are the big tradition. Families clean and repaint tombs, bring flowers and food, and spend the day telling stories of the departed. I wanted to recreate that. The park provided soil, and I shaped and compacted it into a stage and a symbolic grave. I built papier-mâché skeletal pieces, added pigments, flowers, arches, and crosses with the names of real people who passed away. I invited families to decorate the tombs with photos and offerings. Because we share similar immigrant experiences, it was easy to create a meaningful connection.

How do you see your art strengthening communities or preserving identities?

By exposing what we care about, it becomes part of our shared language. Art helps overcome language barriers. In our tradition, we constantly create piñatas, toritos, papier-mâché figures, decorations. It’s embedded in our collective memory. When I invite people to make art, they remember these traditions immediately.

I try to open doors for people, like when families I worked with had their papier-mâché pieces displayed at the Barnes Foundation. Many had never been in a museum before. Public spaces become welcoming when people feel safe, invited, and valued. At celebrations, like our Day of the Dead float at Caliente Nueve, when the city closes streets and supports us, that’s how we feel welcome.

What have you learned about connecting with people through art?

There’s an exchange that happens. We design murals, but we also want people to help paint them. When people feel the space is truly meant for them, they participate. My goal is to awaken the collective memory and remind people that art is already part of who we are. Even when people come from different regions, we connect quickly. Basic human rights and freedom connect us more than anything that divides us. Once people believe they belong in these spaces, they participate fully.

“My goal is to awaken the collective memory and remind people that art is already part of who we are.”

Are there any upcoming projects you’re excited about?

Yes. I want to keep working with my immigrant community. We must keep celebrating and being

visible. I’m currently under contract with Mural Arts to design a mural celebrating Boyz II Men. As an immigrant Mexican artist painting an iconic American R&B group, it’s an honor and a symbol of belonging. Another project is my ongoing collaboration with Ministry of Awe, where I act as a connector with the immigrant community. MoA is the bank, and I’m the branch.

What do you find awe-inspiring?

The journey itself. Being part of something bigger than life. MoA inspires me by transforming a building into a subversive, joyful, experiential space. It’s visionary. Whatever message I want to share about myself, my culture, our stories I can bring to this platform. It’s an invitation for people to join my journey, just as I join theirs.